Introduction

The objective examination is a vital component in the assessment of adolescents and infants with hip pain. The following post outlines key elements in the physical examination to assist clinicians with differential diagnosis. We recommend that you read our previous post the Subjective Examination of Adolescent and Infant Hip to gain a thorough understanding of the causes of hip pain.

Gait

Objective examination should commence with observation of the child’s gait. Clinicians should be suspicious of any child presenting with a limp, walking on their toes (particularly on one leg) or an abnormal gait pattern such as external or internal rotation of the lower limb (Giordano, 2014).

Signs of redness, bruising, swelling or lymphadenopathy around the area of pain should be noted in addition to the child’s general appearance to exclude the presence of any serious pathology (Giordano, 2014).

AROM

Active Range of Motion (AROM) assessment should be performed to assess for any asymmetry. Children with intra – articular hip pathology including femoral acetabular impingement (FAI), stress fractures, labral pathology or hip dysplasia will often find hip flexion, adduction and internal rotation the most pain provocative positions (Jacoby, Yi Meng & Koscher, 2011).

Pain elicited with flexion, abduction and external rotation may indicate impingement from extra-articular anterior structures located superior to the femoral neck such as the iliofemoral ligament or iliopsoas (Walick and Sucato, 2008). Posterior pain with flexion, abduction and external rotation can be associated with sacral pathology (Giordano, 2014).

Children demonstrating hip flexion with lateral femoral deviation require referral for radiological investigation to exclude the presence of a Slipped Upper Femoral Epiphysis (SUFE)(Jacoby et al., 2011).

Manual Muscles Tests

Apophyseal injuries are common in adolescents as the junction of the pelvis, apophysis and soft tissue is an area of considerable weakness following repetitive single leg loading. Manual muscle testing of sartorius, rectus femoris, hamstring and adductor muscles will assist in differential diagnosis between apophysitis and avulsion injuries and allow for appropriate management (Jacoby et al., 2011).

Additionally, resisted abdominal flexion and rotation should be performed to exclude any injury to rectus abdominus, external obliques or conjoint tendon which may contribute to athletic pubalgia (Giordano, 2014).

Palpation

Tenderness on palpation of the ASIS, AIIS, ischial tuberosity and lesser trochanter can be indicative of avulsion fractures caused by a violent contraction of sartorius, rectus femoris, hamstring and iliopsoas muscles, respectively. If the presence of a stress fracture is suspected palpation of the femur, pubic rami, iliac crests and sacroiliac joints are required, as these are the most common sites of injury (Carl, 2012).

Palpation of the lower abdominal quadrant superior to the inguinal ligament should also be performed to exclude non-mechanical causes of hip pain (Jacoby et al., 2011).

X-ray

A referral for AP weight bearing pelvic x-ray should be provided to any children suspected of having intra-articular hip pathology. Below is a list of features to assist with assessment of an A-P pelvis X-ray:

1. Femoral Capital Epiphysis (Increased verticality= increased risk of slippage)

2. Secondary ossification Centre of the greater trochanter

3. Thin bony cortex

4. Tri-radiate Cartilage (Rath, 2014)

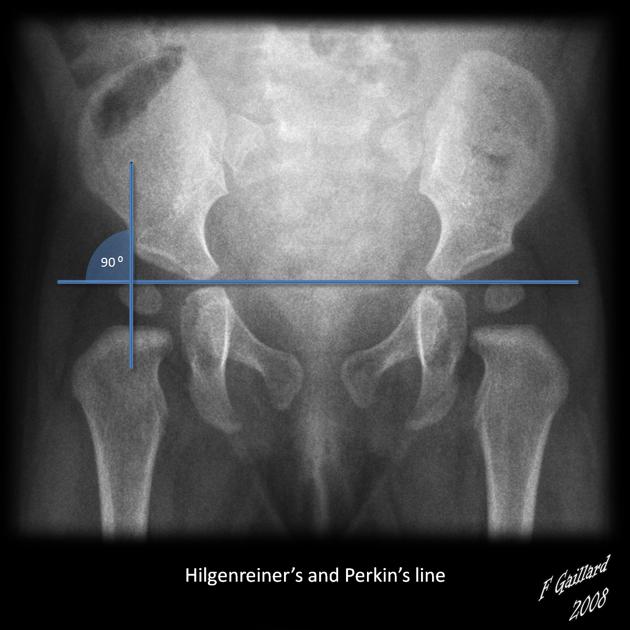

Hilgenreiner’s Line: Connects the superior aspect of the triradiate cartilage (Gallard, 2008)

Perkin’s Line: Connects superior line through acetabular roof (Gallard, 2008)

Shenton’s line: Smooth continuous line between the border of the superior ramus and inferomedial femoral neck (Gallard, 2008)

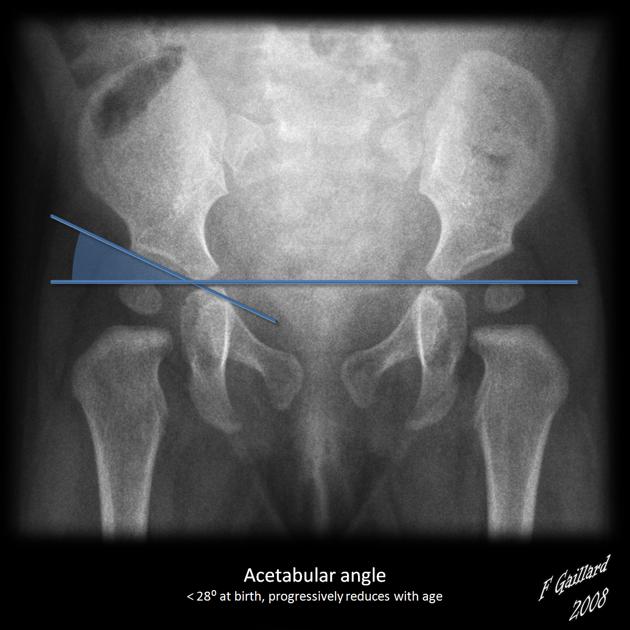

Alpha angle: Formed between the intersection of Hilgereiner’s line and the acetabular roof. O- 10 degrees is considered normal. Increased angle = Increased risk of subluxation (Gallard, 2008).

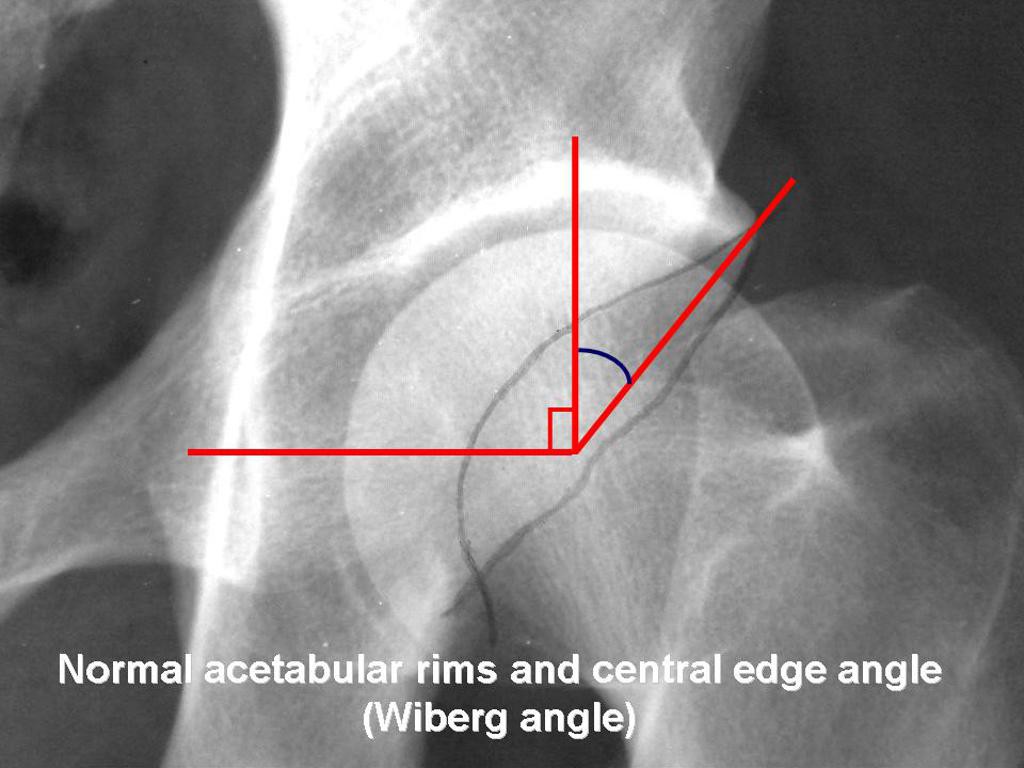

Lateral Central Edge of Angle of Wiberg: Measured from the intersection of vertical line passing through the middle of the femoral head and the lateral edge of the acetabulum. Normal is between 25- 40 degrees. Children with angles less than 16 degrees have decreased surface area for weight bearing and have a poor prognosis (Rath, 2014).

Stay Tuned

Our next blog post will be on the treatment of adolescent and infant hip.

If you have a paediatric or adolescent patient presenting with hip pain that you would like to refer to Little Humans Physio for a consultation, you can contact us or make an online referral

References

Carl, R. (2012). Apophysitis and apophyseal avulsion of the pelvis. International Journal of Athletic Therapy & Training 17(2), 5-9.

Gallard, F. (2015). Developmental dysplasia of the hip. Retrieved from: http://radiopaedia.org/articles/developmental-dysplasia-of-the-hip.

Giordano, B. (2014). Assessment and treatment of hip pain in the adolescent athlete. Pediatric Clinics of North America 61(6), 1137- 1154.

Jacoby, L., Yi-Meng, Y., & Koscher, M. (2011). Hip problems and arthroscopy: Adolescent hip as it relates to sport. Clinical Sports Medicine 30(2), 435-451.

Rath, L. (2014). The developing hip of the adolescent athlete. Adolescents In Sport Symposium.

Walick, K., & Sucato, D. (2008).The adolescent hip and femoroacetabular impingement. Current Orthopaedic Practice,19(6),660-666.